The Urban Death Project

Natural burial solves many of the environmental and ecological problems associated with traditional burial and cremation. Natural burial is carbon neutral, it keeps embalming chemicals out of the soil, and it allows the body to reenter the ecosystem.

But it doesn’t solve the biggest issue with body disposal in urban environments: space.

“I love living in a city, and it seems a little odd that I have to be brought far out of the city to find a natural burial location and be buried that way,” said Katrina Spade, founder and director of the Urban Death Project. “Is there a way to connect us to nature in the city itself? And also have this process that is ritually based in the natural cycle?”

Katrina Spade, founder and director of the Urban Death Project

The answer is yes, Spade believes. And the key to creating systems in which human remains can respectfully reenter the ecosystem in crowded urban environments lies in a simple process familiar to most Americans already: composting.

Based in Seattle, the Urban Death Project is seeking to make human composting a widespread practice. The Project has raised over $90,000 on Kickstarter and recently completed a design for a prototype composting facility. Spade hopes the prototype, which will compost animal corpses, will be completed within next nine to 12 months and will be operated at Washington State University.

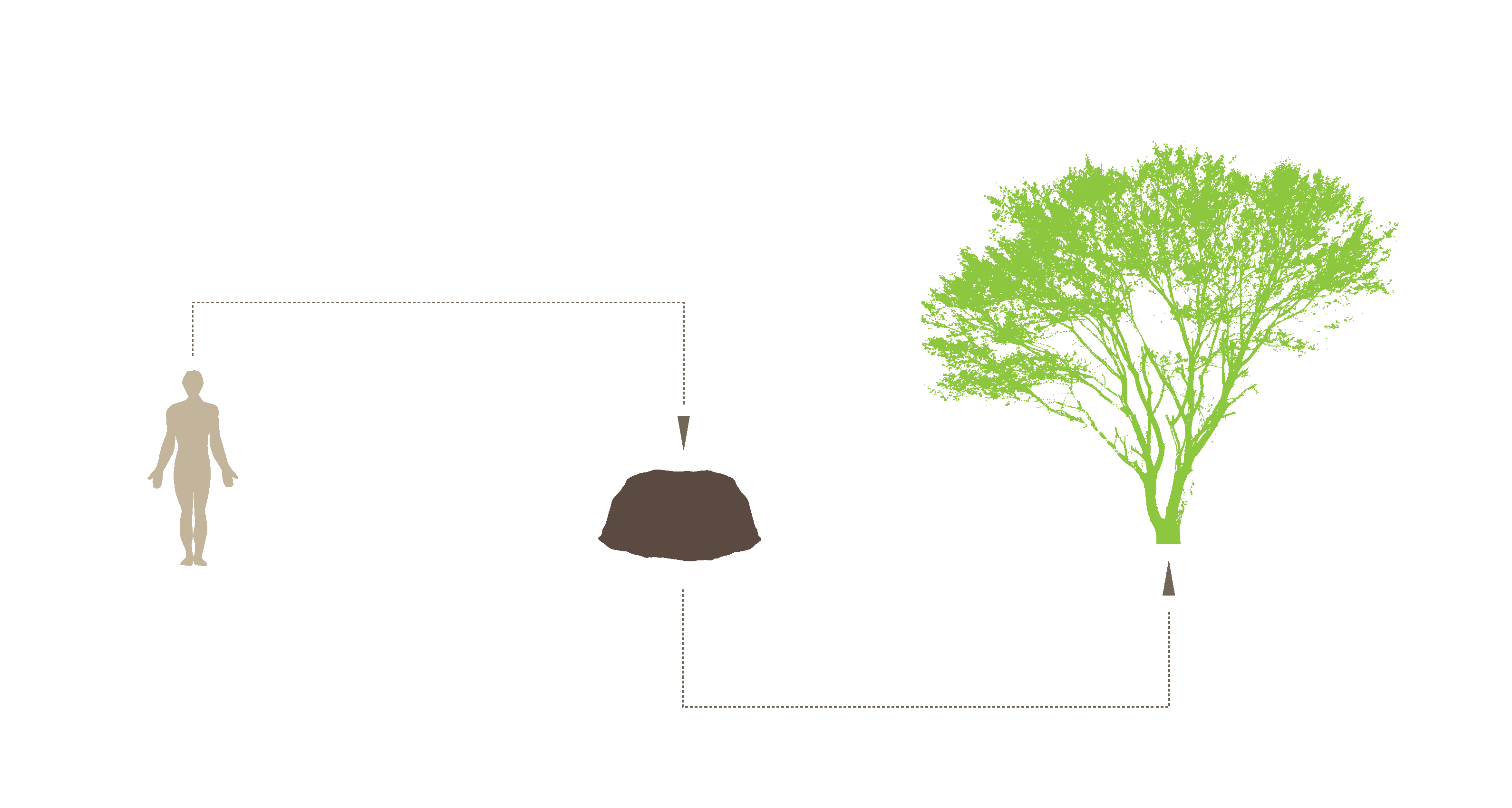

The process would involve mixing human bodies with nitrogen-rich organic material. Over four to six weeks, the bodies would decompose and would each result in a cubic meter of nutrient-rich soil. Loved ones could take that soil and use it to plant trees, or the soil could be added to existing parks. The decomposition process generates heat as the body breaks down – a compost pile can hit 140 degrees Fahrenheit – and would take four to six weeks to create a cubic yard of finished compost.

“It’s not cremation speed, but it’s relatively fast given everything that’s breaking down,” Spade said.

But the process isn’t just about creating compost. Spade wants to change our relationship with death. The finished compost would stay in the community and be used to create garden and green spaces, and the history of human remains in those places would increase respect for them.

Spade envisions a future in which these facilities, which she tentatively calls recomposition centers, would be as ubiquitous as local libraries, and each would be designed to reflect the unique cultural and social characteristics of the communities they belong to. They would also have the advantage of being egalitarian. Spade imagines a sliding payment scale.

“There’s a real social economic issue of not treating all of our dead with the same care and respect,” Spade said. “There is no reason it needs to be like that. So we created a model that basically is accessible to all people.” — Josh Keefe

Artist rendering by Urban Death Project